Keeping Track of Changes

Last updated on 2023-09-07 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 40 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do I make changes to a project without losing or breaking things?

- Why does GitHub exist?

Objectives

- List common problems with introducing changes to files without tracking

- Understand good practices in tracking changes

- Write a good change description

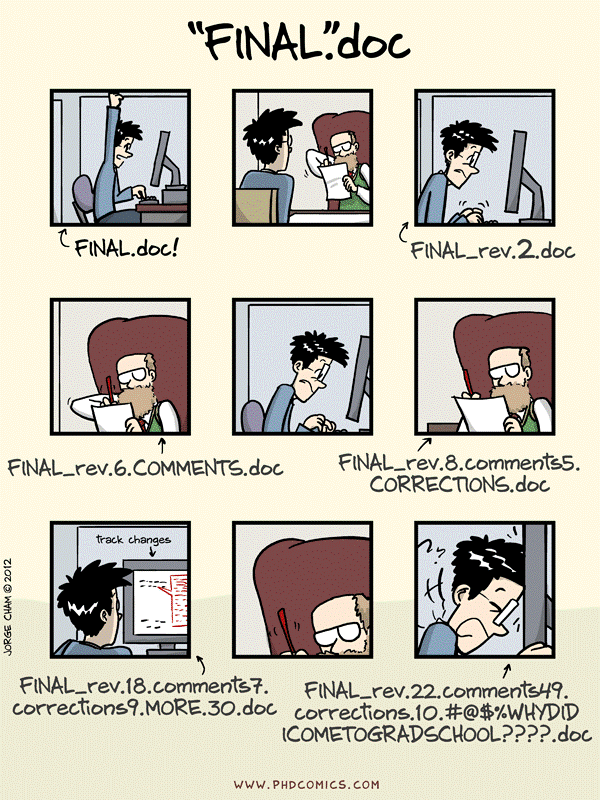

Problems with change

Which of this issues can you relate to?

- I have fifteen versions of this file and I don’t know which is which

- I can’t remake this figure from last year

- I modified my code and something apparently unrelated does not work anymore

- I have several copies of the same directory because I’m worried about breaking something

- Somebody duplicated a record in a shared file with samples

- You remember seeing a data file but cannot find it anymore: is it deleted ? Moved away ?

- I tried multiple analysis and I don’t remember which one I chose to generate my output data

- I have to merge changes to a paper from mails with collaborators

- I accidently deleted a part of my work

- I came to an old project and forgot where I left it

- I have trouble to find the source of a mistake in an experiment

- My directory is polluted with a lot of unused/temporary/old folders because I’m afraid of losing something important

- I made a lot of changes to my paper but only want to bring back one of paragraph

Keeping track of changes that you or your collaborators make to data and software is a critical part of research. Being able to reference or retrieve a specific version of the entire project aids in reproducibility for you leading up to publication, when responding to reviewer comments, and when providing supporting information for reviewers, editors, and readers.

We believe that the best tools for tracking changes are the version control systems that are used in software development, such as Git, Mercurial, and Subversion. They keep track of what was changed in a file when and by whom, and synchronize changes to a central server so that many users can manage changes to the same set of files.

While these version control tools make tracking changes easier, they can have a steep learning curve. So, we provide two sets of recommendations:

- a systematic manual approach for managing changes and

- version control in its full glory,

and you can use the first while working towards the second, or just jump in to version control.

Whatever system you chose, we recommend that you:

Back up (almost) everything created by a human being as soon as it is created

This includes scripts and programs of all kinds, software packages that your project depends on, and documentation. A few exceptions to this rule are discussed below.

Keep changes small

Each change should not be so large as to make the change tracking irrelevant. For example, a single change such as “Revise script file” that adds or changes several hundred lines is likely too large, as it will not allow changes to different components of an analysis to be investigated separately. Similarly, changes should not be broken up into pieces that are too small. As a rule of thumb, a good size for a single change is a group of edits that you could imagine wanting to undo in one step at some point in the future.

Share changes frequently

Everyone working on the project should share and incorporate changes from others on a regular basis. Do not allow individual investigator’s versions of the project repository to drift apart, as the effort required to merge differences goes up faster than the size of the difference. This is particularly important for the manual versioning procedure described below, which does not provide any assistance for merging simultaneous, possibly conflicting, changes.

Create, maintain, and use a checklist for saving and sharing changes to the project

The list should include writing log messages that clearly explain any changes, the size and content of individual changes, style guidelines for code, updating to-do lists, and bans on committing half-done work or broken code. See [gawande2011] for more on the proven value of checklists.

Store each project in a folder that is mirrored off the researcher’s working machine

This may include:

- using a shared system such as a (institutional) cloud or shared drive, or

- a remote version control repository such as GitHub.

Synchronize that folder at least daily. It may take a few minutes, but that time is repaid the moment a laptop is stolen or its hard drive fails.

How to document a change

A good entry that documents changes should contain:

- Date of the change

- Author of the change

- List of affected files

- A short description of the nature of the introduced changes AND/OR motivation behind the change.

Examples of the descriptions are:

Added flow cytometry data for the control and starvation stressed samples

Updated matplot library to version 3.4.3 and regenerated figures

Added pane with protein localization to the Figure 3 and its discussion in the text

Reverted to the previous version of the abstract text as the manuscript reached word limits

Cleaned the strain inventory: Recent freezer cleaning and ordering indicated a lot of problem with the strains data. The missing physical samples were removed from the table, the duplicated ids are marked for checking with PCR. The antibiotic resistance were moved from phenotype description to its own column.

New regulation heatmap: As suggested by Will I used the normalization and variance stabilization procedure from Hafemeister et al prior to clustering and heatmap generation

The larger the project (measured either in: collaborators, file numbers, or workflow complexity) the more detailed the change description should be. While your personal project can get away with one liner descriptions, the largest projects should always contain information about motivation behind the change and what are the consequences.

Manual Versioning

Our first suggested approach, in which everything is done by hand, has two additional parts:

-

Add a file called

CHANGELOG.txtto the project’sdocssubfolder, and make dated notes about changes to the project in this file in reverse chronological order (i.e., most recent first). This file is the equivalent of a lab notebook, and should contain entries like those shown below.

## 2016-04-08

* Switched to cubic interpolation as default.

* Moved question about family's TB history to end of questionnaire.

## 2016-04-06

* Added option for cubic interpolation.

* Removed question about staph exposure (can be inferred from blood test results).- Copy the entire project whenever a significant change has been made (i.e., one that materially affects the results), and store that copy in a sub-folder whose name reflects the date in the area that’s being synchronized. This approach results in projects being organized as shown below:

.

|-- project_name

| -- current

| -- ...project content as described earlier...

| -- 2016-03-01

| -- ...content of 'current' on Mar 1, 2016

| -- 2016-02-19

| -- ...content of 'current' on Feb 19, 2016Here, the project_name folder is mapped to external

storage (such as Dropbox), current is where development is

done, and other folders within project_name are old

versions.

Data is Cheap, Time is Expensive

Copying everything like this may seem wasteful, since many files won’t have changed, but consider: a terabyte hard drive costs about \$50, which means that 50 GByte costs less than \$5. Provided large data files are kept out of the backed-up area (discussed below), this approach costs less than the time it would take to select files by hand for copying.

This manual procedure satisfies the requirements outlined above without needing any new tools. If multiple researchers are working on the same project, though, they will need to coordinate so that only a single person is working on specific files at any time. In particular, they may wish to create one change log file per contributor, and to merge those files whenever a backup copy is made.

Version Control Systems

What the manual process described above requires most is self-discipline. The version control tools that underpin our second approach—the one we use in our own projects–don’t just accelerate the manual process: they also automate some steps while enforcing others, and thereby require less self-discipline for more reliable results.

- Use a version control system, to manage changes to a project.

Box 2 briefly explains how version control systems work. It’s hard to know what version control tool is most widely used in research today, but the one that’s most talked about is undoubtedly Git. This is largely because of GitHub, a popular hosting site that combines the technical infrastructure for collaboration via Git with a modern web interface. GitHub is free for public and open source projects and for users in academia and nonprofits. GitLab is a well-regarded alternative that some prefer, because the GitLab platform itself is free and open source. Bitbucket provides free hosting for both Git and Mercurial repositories, but does not have nearly as many scientific users.

Box 2: How Version Control Systems Work

A version control system stores snapshots of a project’s files in a repository. Users modify their working copy of the project, and then save changes to the repository when they wish to make a permanent record and/or share their work with colleagues. The version control system automatically records when the change was made and by whom along with the changes themselves.

Crucially, if several people have edited files simultaneously, the version control system will detect the collision and require them to resolve any conflicts before recording the changes. Modern version control systems also allow repositories to be synchronized with each other, so that no one repository becomes a single point of failure. Tool-based version control has several benefits over manual version control:

Instead of requiring users to make backup copies of the whole project, version control safely stores just enough information to allow old versions of files to be re-created on demand.

Instead of relying on users to choose sensible names for backup copies, the version control system timestamps all saved changes automatically.

Instead of requiring users to be disciplined about completing the changelog, version control systems prompt them every time a change is saved. They also keep a 100% accurate record of what was actually changed, as opposed to what the user thought they changed, which can be invaluable when problems crop up later.

Instead of simply copying files to remote storage, version control checks to see whether doing that would overwrite anyone else’s work. If so, they facilitate identifying conflict and merging changes.

Changelog in action

Have a look at one of the example github repositories and how they track changes:

Give examples of:

- what makes their changelogs good?

- what could be improved?

Also, what would be the most difficult feature to replicate with manual version control?

Some good things:

- all log entries contain date and author

- all log entries contain list of files that have been modified

- for text files the actual change can be visible

- the description text gives an idea of the change

Some things that could be improved:

- The pigs files should probably be recorded in smaller chunks (commits). The raw data and cleaned data could be added separetely unless they all were captured at the same time.

- Rather than general “Readme update” a more specific descriptin could be provied “Reformated headers and list”

- Some of the Ballou et al changes could do with more detailed descriptions, for example why the change took place in case of IQ_TREE entries

Something difficult to replicate manually:

- The changelog is linked to a complete description of the file changes.

- Click on an entry, for example

Clarify README.mdorupdate readme file, and you’ll see the file changes with additions marked with + (in green) and deletions marked with - (in red).

What Not to Put Under Version Control

The benefits of version control systems don’t apply equally to all

file types. In particular, version control can be more or less rewarding

depending on file size and format. First, file comparison in version

control systems is optimized for plain text files, such as source code.

The ability to see so-called “diffs” is one of the great joys of version

control systems. Unfortunately, Microsoft Office files (like the

.docx files used by Word) or other binary files, e.g.,

PDFs, can be stored in a version control system, but it is not always

possible to pinpoint specific changes from one version to the next.

Tabular data (such as CSV files) can be put in version control, but

changing the order of the rows or columns will create a big change for

the version control system, even if the data itself has not changed.

Second, raw data should not change, and therefore should not require version tracking. Keeping intermediate data files and other results under version control is also not necessary if you can re-generate them from raw data and software. However, if data and results are small, we still recommend versioning them for ease of access by collaborators and for comparison across versions.

Third, today’s version control systems are not designed to handle megabyte-sized files, never mind gigabytes, so large data or results files should not be included. (As a benchmark for “large”, the limit for an individual file on GitHub is 100MB.) Some emerging hybrid systems such as Git LFS put textual notes under version control, while storing the large data itself in a remote server, but these are not yet mature enough for us to recommend.

Inadvertent Sharing

Researchers dealing with data subject to legal restrictions that prohibit sharing (such as medical data) should be careful not to put data in public version control systems. Some institutions may provide access to private version control systems, so it is worth checking with your IT department.

Additionally, be sure not to unintentionally place security credentials, such as passwords and private keys, in a version control system where it may be accessed by others.

Attribution

This episode was adapted from and includes material from Wilson et al. Good Enough Practices for Scientific Computing.

- Small, frequent changes are easier to track

- Tracking change systematically with checklists is helpful

- Version control systems help adhere to good practices