Writing Scripts and Working with Data

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can we automate a commonly used set of commands?

How can we transfer files between local and remote computers?

Objectives

Use the

nanotext editor to modify text files.Write a basic shell script.

Use the

bashcommand to execute a shell script.Use

chmodto make a script an executable program.

Writing files

We have been able to do much work with existing files, but what if we want to write our own files? We are not going to type in a FASTA file, but we will see as we go through other tutorials; there are many reasons we will want to write a file or edit an existing file.

We will use a text editor called Nano to add text to files. We are going to create a file to take notes about what we have been doing with the data files in ~/dc_workshopd/data/untrimmed_fastq.

Taking notes is good practice when working in bioinformatics. We can create a file called a README.txt that describes the data files in the directory or documents how the files in that directory were generated. As the name suggests, it is a file that others should read to understand the information in that directory.

Let’s change our working directory to ~/dc_workshop/data/untrimmed_fastq using cd,

then run nano to create a file called README.txt:

$ cd ~/dc_workshop/data/untrimmed_fastq

$ nano README.txt

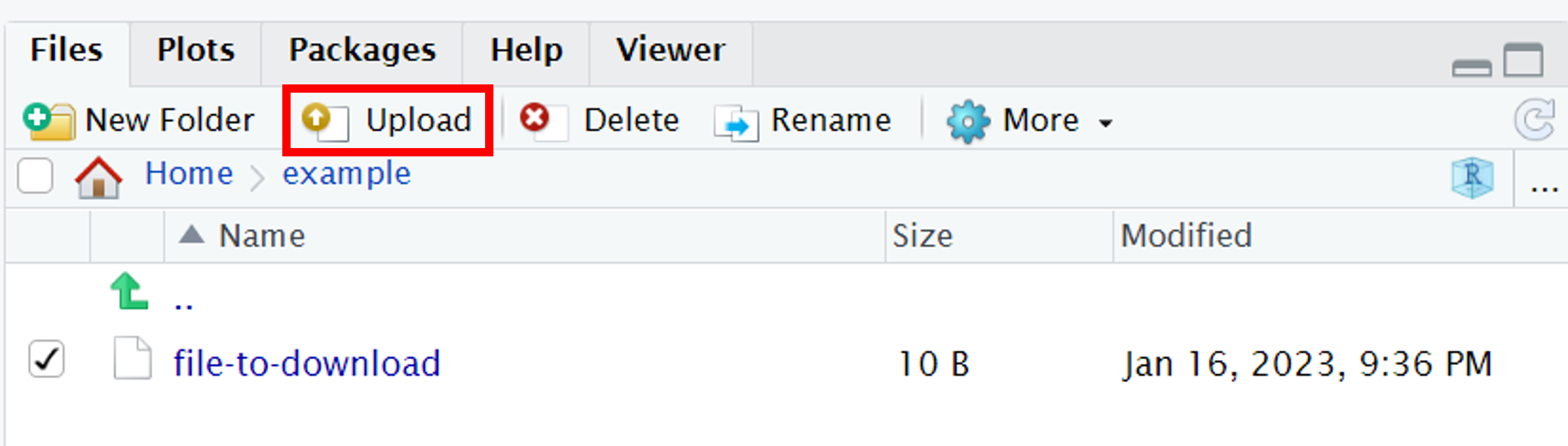

You should see something like this:

Figure 1. GNU Nano Text Editor Menu.

Figure 1. GNU Nano Text Editor Menu.

The text at the bottom of the screen shows the keyboard shortcuts for performing various tasks in nano. We will talk more about how to interpret this information soon.

Which Editor?

When we say, “

nanois a text editor,” we really do mean “text”: it can only work with plain character data, not tables, images, or any other human-friendly media. We use it in examples because it is one of the least complex text editors. However, because of this trait, it may not be powerful enough or flexible enough for the work you need to do after this workshop. On Unix systems (such as Linux and Mac OS X), many programmers use Emacs or Vim (both of which require more time to learn), or a graphical editor such as Gedit. On Windows, you may wish to use Notepad++. Windows also has a built-in editor callednotepadthat can be run from the command line in the same way asnanofor the purposes of this lesson.No matter what editor you use, you need to know where it searches for and saves files. If you start it from the shell, it will (probably) use your current working directory as its default location. If you use your computer’s start menu, it may want to save files in your desktop or documents directory instead. You can change this by navigating to another directory the first time you “Save As…”

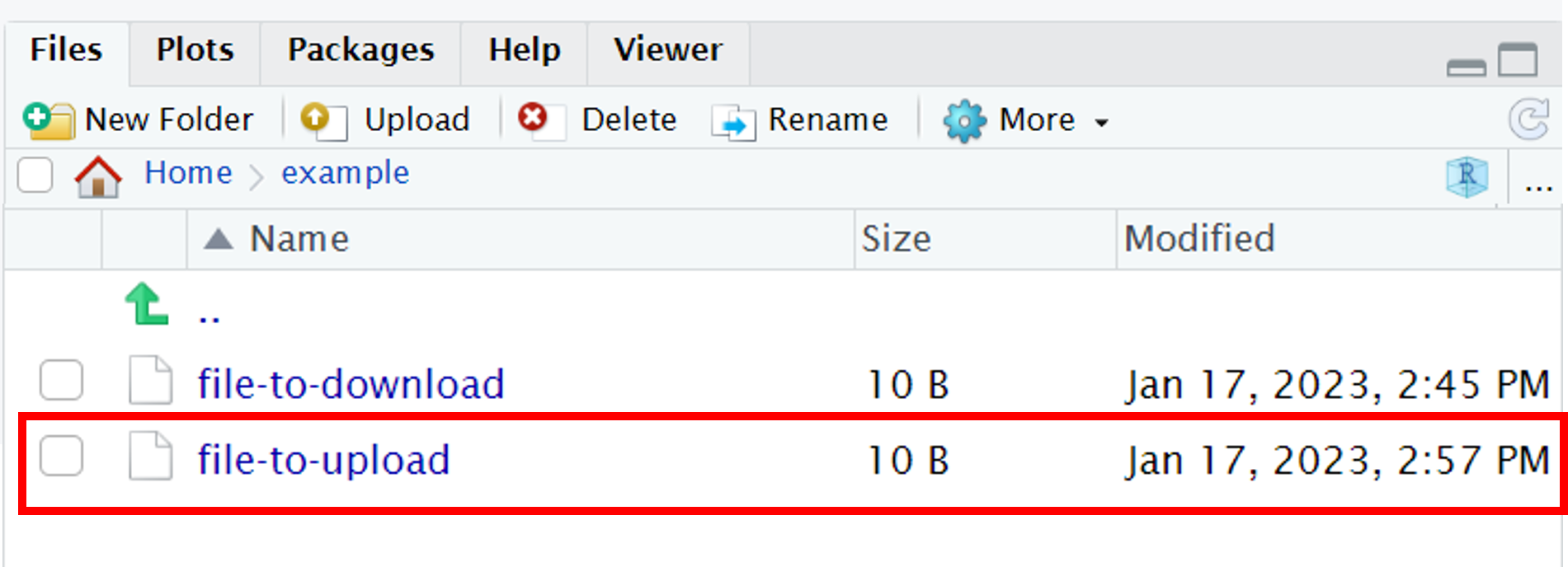

Let us type in a few lines of text. Describe the files in this directory or what you have been doing with them.

Figure 2. For example, the README file is written in nano.

Figure 2. For example, the README file is written in nano.

Once we are happy with our text, we can press Ctrl-O (press the Ctrl or Control key and, while

holding it down, press the O key) to write our data to disk. You will be asked what file we want to save this to:

Press Return to accept the suggested default of README.txt.

Once our file is saved, we can use Ctrl-X to quit the editor and return to the shell.

Control, Ctrl, or ^ Key

The Control key is also called the “Ctrl” key. There are various ways in which using the Control key may be described. For example, you may see an instruction to press the Ctrl key and, while holding it down, press the X key, described as any of:

Control-XControl+XCtrl-XCtrl+X^XC-xIn

nano, along the bottom of the screen, you will see^G Get Help ^O WriteOut. This means that you can use Ctrl-G to get help and Ctrl-O to save your file.

Now you have written a file. You can look at it with less or cat, or open it up again and edit it with nano.

Exercise 1: Edit a file with nano

Open

README.txt, add the date to the top of the file, and save the file.Solution

Use `nano README.txt` to open the file. Add today's date and then use <kbd>Ctrl</kbd>-<kbd>X</kbd> to exit and `y` to save.

Writing scripts

A really powerful thing about the command line is that you can write scripts. Scripts let you save commands to run them and also lets you put multiple commands together. Though writing scripts may require an additional time investment initially, this can save you time as you run them repeatedly. Scripts can also address the challenge of reproducibility: if you need to repeat analysis, you retain a record of your command history within the script.

One thing we will commonly want to do with sequencing results is pull out bad reads and write them to a file to see if we can figure out what is going on with them. We are going to look for reads with long sequences of N’s like we did before, but now we are going to write a script, so we can run it each time we get new sequences rather than type the code in by hand each time.

Bad reads have a lot of N’s, so we are going to look for NNNNNNNNNN with grep. We want the whole FASTQ record, so we are also going to get the one line above the sequence and the two lines below. We also want to look at all the files that end with .fastq, so we will use the * wildcard.

grep -B1 -A2 NNNNNNNNNN *.fastq > scripted_bad_reads.txt

We are going to create a new file to put this command in. We will call it bad-reads-script.sh. The sh is not required, but using that extension tells us it is a shell script.

$ nano bad-reads-script.sh

Type your grep command into the file and save it as before. Be careful not to add the $ at the beginning of the line.

Now comes the neat part. We can run this script. Type:

$ bash bad-reads-script.sh

It will look like nothing happened, but now if you look at scripted_bad_reads.txt, you can see that there are now reads in the file.

Exercise 2: Edit a script

We want the script to tell us when it is done.

Solution

1. Open `bad-reads-script.sh` and add the line `echo "Script finished!"` after the `grep` command and save the file. 2. Run the updated script.

Making the script into a program

We had to type bash because we needed to tell the computer what program to use to run this script. Instead, we can turn this script into its own program. We need to tell it that it is a program by making it executable. We can do this by changing the file permissions. We talked about permissions in an earlier episode.

First, let us look at the current permissions.

$ ls -l bad-reads-script.sh

-rw-rw-r-- 1 dcuser dcuser 0 Oct 25 21:46 bad-reads-script.sh

We see that it says -rw-r--r--. This combination shows that the file can be read by any user and written to by the file owner (you). We want to change these permissions so the file can be executed as a program. We use the command chmod as we did earlier when we removed write permissions. Here we are adding (+) executable permissions (+x).

$ chmod +x bad-reads-script.sh

Now let us look at the permissions again.

$ ls -l bad-reads-script.sh

-rwxrwxr-x 1 dcuser dcuser 0 Oct 25 21:46 bad-reads-script.sh

Now we see that it says -rwxr-xr-x. The x’s there now tell us we can run it as a program. So, let us try it! We will need to put ./ at the beginning, so the computer knows to look here in this directory for the program.

$ ./bad-reads-script.sh

The script should run the same way as before, but now we have created our own computer program!

It is good practice to keep any large files compressed while not using them. In this way, you save storage space; you will see that you will appreciate it when you advance your analysis. So, since we will not use the FASTQ files for now, let us compress them. Moreover, run ls -lh to confirm that they are compressed.

$ gzip ~/dc_workshop/data/untrimmed_fastq/*.fastq

$ ls -lh ~/dc_workshop/data/untrimmed_fastq/*.fastq.gz

total 428M

-rw-r--r-- 1 dcuser dcuser 24M Nov 26 12:36 JC1A_R1.fastq.gz

-rw-r--r-- 1 dcuser dcuser 24M Nov 26 12:37 JC1A_R2.fastq.gz

-rw-r--r-- 1 dcuser dcuser 179M Nov 26 12:44 JP4D_R1.fastq.gz

-rw-r--r-- 1 dcuser dcuser 203M Nov 26 12:51 JP4D_R2.fastq.gz

Moving and downloading data

So far, we have worked with pre-loaded data on the instance in the cloud. Usually, however, most analyses begin with moving data onto the instance. Below we will show you some commands to download data onto your instance or to move data between your computer and the cloud.

Getting data from the cloud

Two programs will download data from a remote server to your local

(or remote) machine: wget and curl. They were designed to do slightly different

tasks by default, so you will need to give the programs somewhat different options to get

the same behavior, but they are mostly interchangeable.

-

wgetis short for “world wide web get”, and its basic function is to download -

cURLis a pun. It is supposed to be read as “see URL”, so its primary function is to display webpages or data at a web address.

Which one you need to use mainly depends on your operating system, as most computers will only have one or the other installed by default.

Let us say you want to download some data from Ensembl. We will download a tiny

tab-delimited file that tells us what data is available on the Ensembl bacteria server.

Before starting our download, we need to know whether we are using curl or wget.

To see which program you have, type:

$ which curl

$ which wget

which is a BASH program that looks through everything you have

installed and tells you what folder it is installed to. If it cannot

find the program you asked for, it returns nothing, i.e., it gives you no

results.

On Mac OSX, you will likely get the following output:

$ which curl

/usr/bin/curl

$ which wget

$

This output means that you have curl installed but not wget.

Once you know whether you have curl or wget use one of the

following commands to download the file:

$ cd

$ wget ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/release-37/bacteria/species_EnsemblBacteria.txt

or

$ cd

$ curl -O ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/release-37/bacteria/species_EnsemblBacteria.txt

Since we wanted to download the file rather than view it, we used wget without

any modifiers. With curl however, we had to use the -O flag, which simultaneously tells curl to

download the page instead of showing it to us and specifies that it should save the

file using the same name it had on the server: species_EnsemblBacteria.txt

It’s important to note that both curl and wget download to the computer that the

command line belongs to. So, if you are logged into AWS on the command line and execute

the curl command above in the AWS terminal, the file will be downloaded to your AWS

machine, not your local one.

Moving files between your laptop and your instance

What if the data you need is on your local computer, but you need to get it into the cloud? There are several ways to do this. While following this lesson, you may be using the RStudio interface containing a terminal, some other terminal, or your own local computer. Depending on your setup, there are several alternatives to transfer the files. Here we describe how to use the RStudio interface to transfer files..

Transferring files scenarios

- If you are working on your local computer, there is no need to transfer files because you already have them locally.

In that case, you only need to know the directory you are working in.- If you are working on a remote machine such as an AWS instance, you can use the

scpcommand. In that case, it is always easier to start the transfer locally. If you are typing into a terminal, the terminal should not be logged into your instance. It should show your local computer. If you are using a transfer program, it needs to be installed on your local machine, not your instance.- If you are using the RStudio server from the AWS instance, you can transfer files between your local and your remote machine using the graphic interface of RStudio.

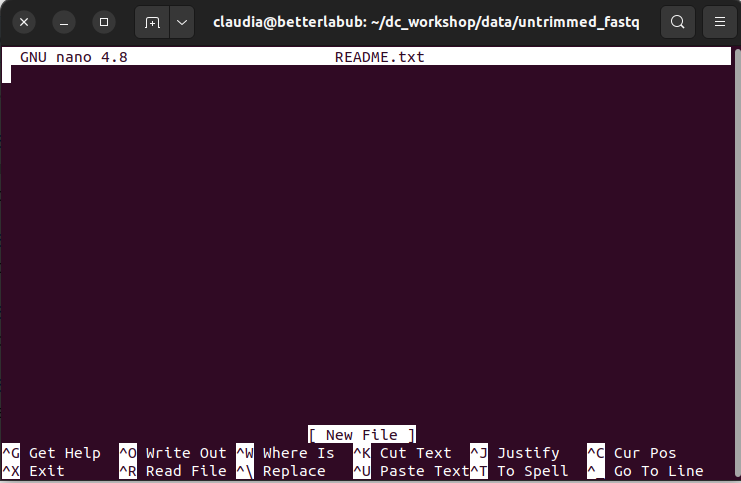

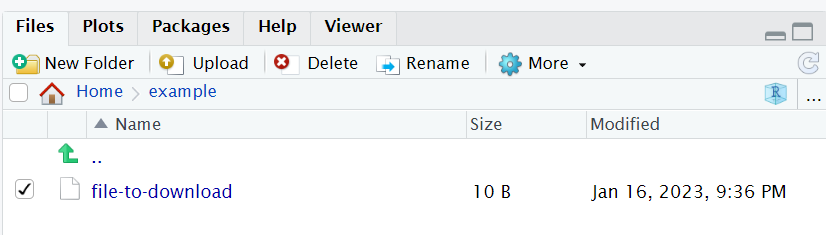

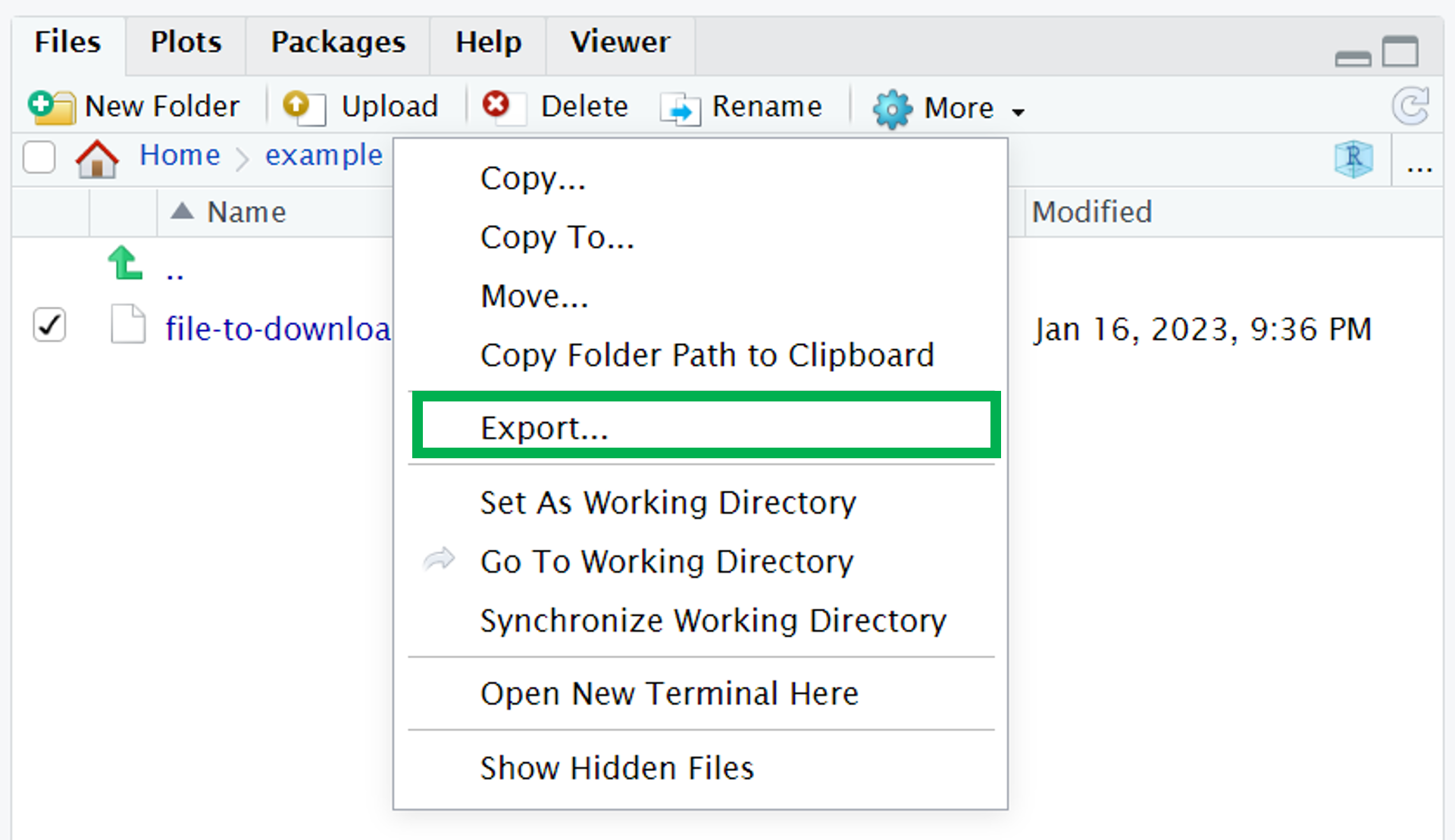

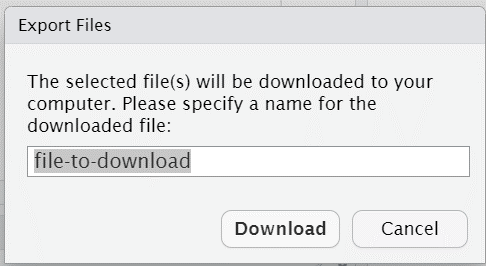

Downloading files in RStudio

We will follow the next five steps to download files with the RStudio interface.

-

First, we select the file to download from the bottom right panel.

-

Then, we choose “More” to display more actions for the selected file.

-

Within the “More” menu, the “export” button should become available.

-

An emergent window should be displayed on your screen where you can select the “Download” option.

-

Your file should now be downloaded to your local computer.

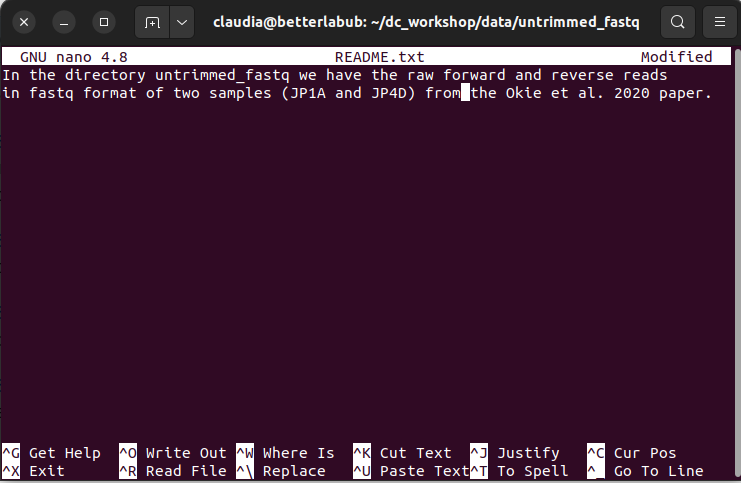

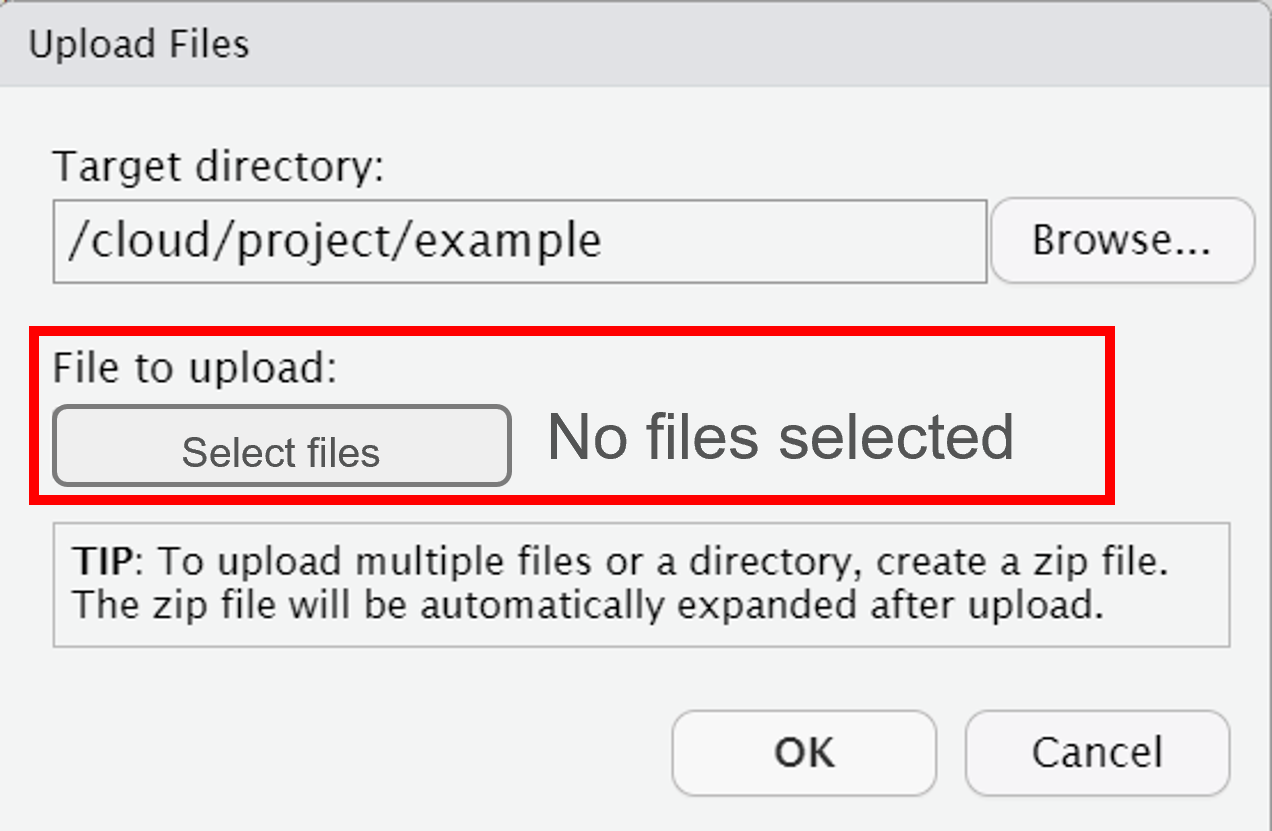

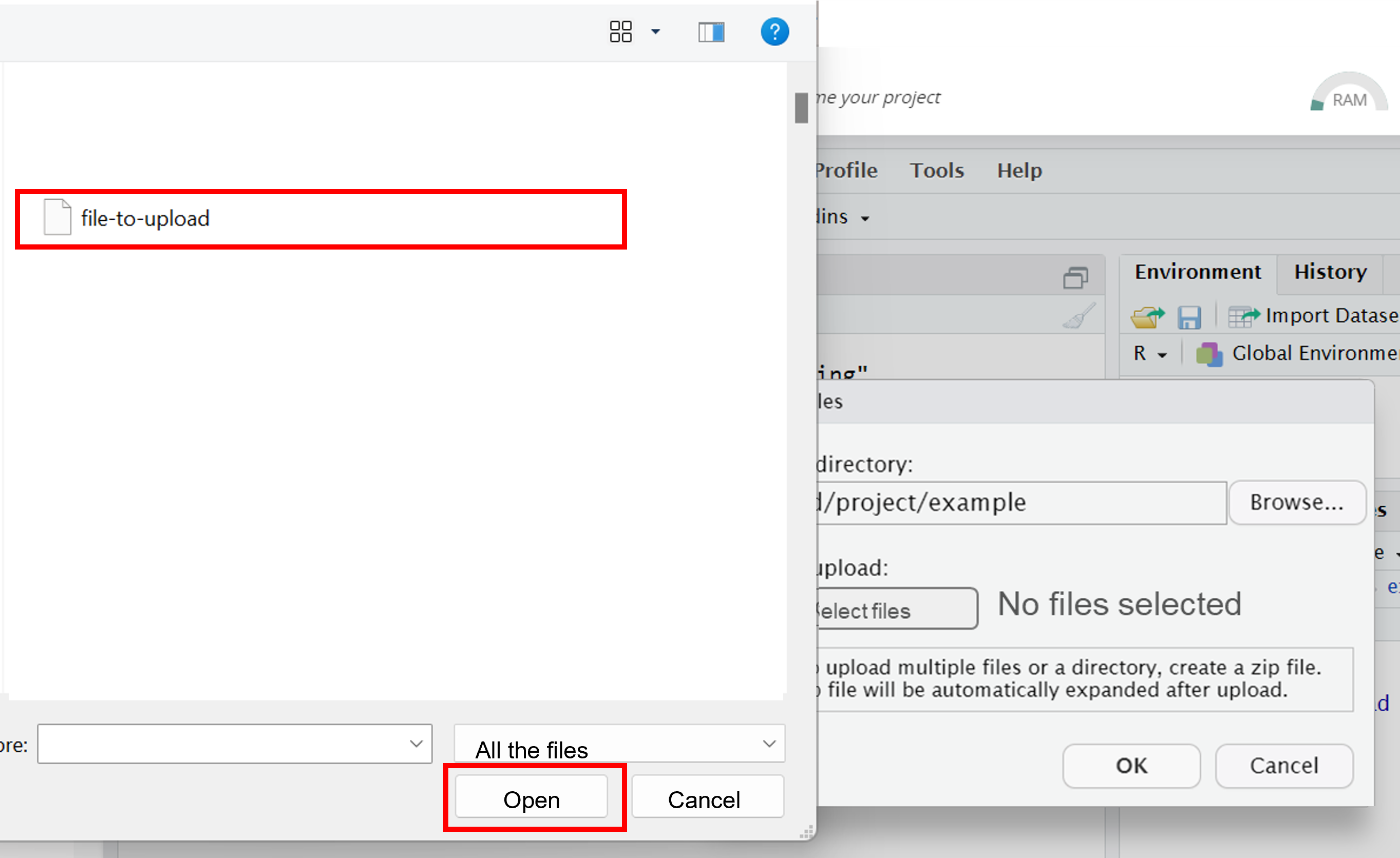

Upload files to AWS in RStudio

Now that we learned how to download files from the RStudio interface, we will learn the opposite action, uploading files from your local computer to your remote AWS machine.

-

After an emergent window is displayed on your screen, select “Select file”.

-

A new screen is displayed on your computer where you should choose the file to upload. Choose the file and click “open”.

-

Finally, if the file is correct, click “ok,” and the uploading will start.

Transferring data between your local and virtual machine with scp

scp stands for ‘secure copy protocol’ and is a widely used UNIX tool for moving files

between computers. The simplest way to use scp is to run it in your local terminal

and use it to copy a single file. While scp <local-file-path> <AWS instance path> will upload a local file into your AWS instance,

scp <AWS-instance-path> <local-file-path> will move your file from your remote AWS instance into

your local computer. The general form of the scp command is the following:

$ scp <file you want to move, local or remote> <path to where I want to move it, local or remote>

Exercise 3: Uploading data with

scpLet us download the text file

~/data/untrimmed_fastq/scripted_bad_reads.txtfrom the remote machine to your local computer. Which of the following commands would download the file?

A)$ scp local_file.txt dcuser@ip.address:/home/dcuser/B)

$ scp dcuser@ip.address:/home/dcuser/dc_workshop/data/untrimmed_fastq/scripted_bad_reads.txt. ~/DownloadsSolution

A) False. This command will upload the file

local_file.txtto the dcuser home directory in your AWS remote machine.

B) True. This option downloads the bad reads file in~/data/scripted_bad_reads.txtto your local~/Downloadsdirectory (make sure you use substitute dcuser@ ip.address with your remote login credentials)

Key Points

Scripts are a collection of commands executed together.

Scripts are executable text files.

Nano is a text editor.

In a terminal,

scptransfers information to and from virtual and local computers.R studio remote interface allows the transfer of information between virtual and local computers.