Data Tidiness

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

What metadata should I collect?

How should I structure my sequencing data and metadata?

Which ethical considerations involve microbiome data and metadata?

Objectives

Think about and understand the types of metadata a sequencing experiment will generate.

Understand the importance of metadata and potential metadata standards.

Explore common formatting challenges in spreadsheet data.

Consider confidentiality issues that may arise from storing and sharing the metadata.

When we think about the data for a sequencing project, we often start by thinking about the sequencing data that we get back from the sequencing center, but just as important, if not more so, is the data you have generated about the sequences before they ever go to the sequencing center. Data about the data are often called the metadata. The sequence data itself is useless without the information about what you sequenced.

Discussion 1

With the person next to you, discuss:

What kinds of data and information have you generated before you sent your DNA/RNA off for sequencing?

Solution

Types of files and information you have generated:

- Spreadsheet or tabular data with the data from your experiment and whatever you were measuring for your study.

- Lab notebook notes about how you conducted those experiments.

- Spreadsheet or tabular data about the samples you sent for sequencing. Sequencing centers often have a particular format they need with the name of the sample, DNA concentration, and other information.

- Lab notebook notes about how you prepared the DNA/RNA for sequencing and what type of sequencing you are doing, e.g., paired-end Illumina HiSeq. There likely will be other ideas here too. Was this more information and data than you were expecting?

All the data and information discussed can be considered metadata, i.e., data about the data. We want to follow a few guidelines for metadata.

Notes about your experiment

Notes about your experiment, including how you prepared your samples for sequencing, should be in your lab notebook, whether a physical lab notebook or an electronic one. For guidelines on good lab notebooks, see the Howard Hughes Medical Institute “Making the Right Moves: A Practical Guide to Scientifıc Management for Postdocs and New Faculty” the section on Data Management and Laboratory Notebooks.

Including dates on your lab notebook pages, the samples themselves, and in any records about those samples help you associate everything with each other later. Using dates also helps create unique identifiers because even if you process the same sample twice, you do not usually do it on the same day, or if you do, you are aware of it and give them names like A and B.

Unique identifiers

Unique identifiers are unique names for a sample or set of sequencing data. They are names for that data that only exist for that data. Having these unique names makes them much easier to track later.

Metadata: Data about the experiment

Data about the experiment is usually collected in spreadsheets, like Excel. Alongside the spreadsheet, creating a text file called README is convenient. This file holds information about the research project, how the samples were generated, and how to read the metadata spreadsheet. This information is very convenient when working on a team, and more people join the project even at different experiment steps. This order may help better your collaborators to easily understand what the data is about.

Metadata standards

The kind of data you would collect depends on your experiment; often, there are guidelines from metadata standards. Many fields have particular ways that they structure their metadata, so it is consistent and can be used across the area. The Digital Curation Center maintains a list of metadata standards and some that are particularly relevant for genomics data are available from the Genomics Standards Consortium. In particular, assembly quality and an estimate of genome completeness and contamination are standards for Metagenome-Assambled-Genomes (MAGs).

Cornell University gives us a useful guide and template file to write README-style metadata in case there are no metadata standards for your type of data. When you submit data to an organization, they may give you a file with specifications about

the metadata needed for their platform. For example, MG-RAST gives a file like this.

Discussion 2. What information would you write in your README file?

Suppose that in your field, there are no metadata standards yet. Think about the minimum amount of information that someone would need to be able to work with your data without talking to you. What type of information would you put in your README file?

Solution

Some examples of clarifications that need to be written in the README are:

- Date format (mm-dd-yyyy or dd-mm-yyyy, for example).

- Meaning of abbreviations.

- Meaning or pattern followed to construct the unique IDs of samples.

- Details about the methodology.

- Contact information about the persons who performed the collection and/or experiments.

- Meaning of each variable name.

Discussion 3: Ethical considerations in microbiome studies

The microbiomes knowledge is human’s global heritage and must be ruled by ethical principles such as do good, do not harm, respect, and act justly. While studying the human microbiome, there are particular concerns. For example, if you discover an infection such as HIV in the blood microbiome, would you inform the participants? What If they did not want to know? Following these principles, what other ethical considerations can you think about human microbiomes?

Solution

- Respect: Ask participants to sign explicit prior informed consent.

- Do good: Share the data but protect participant’s privacy

- Do no harm: establish a policy about results communications.

- Do no harm: Consider the Invasiveness of sampling and minimize the risk

- Act justly: Favor diversity of subjects and justice

More information about these topics is developed by Mc Guire et al. 2008 in the paper:Ethical, legal, and social considerations in conducting the Human Microbiome Project and by Lange et al. 2022 in: Microbiome ethics, guiding principles for microbiome research, use and knowledge management’

Structuring data in spreadsheets

Independent of the type of data you are collecting, there are standard ways to enter that data into the spreadsheet to make it easier to analyze later. We often enter data that makes it easy for us as humans to read and work with it because we are human! Computers need data structured in a way that they can use it. So to use this data in a computational workflow, we need to think like computers when we use spreadsheets.

The cardinal rules of using spreadsheet programs for data:

- Leave the raw data raw - do not change it!

- Put each observation in its own row. An observation is each of our samples, the subjects for which we store information in the spreadsheet.

- Put all your variables in columns. The variables are the different pieces of information that we have about our sample (its genotype, phenotype, treatment, etc.).

- Have column names explanatory but without spaces. Use ‘-‘, ‘_’ or camel case instead of a space. For instance, ‘library-prep-method’ or ‘LibraryPrep’is better than ‘library preparation method’ or ‘prep’, because computers interpret spaces in particular ways.

- Do not combine multiple pieces of information in one cell. Sometimes it just seems like one thing, but think if that is the only way you will want to be able to use or sort that data. For example, instead of having a column with species and strain name (e.g., E. coli K12) you would have one column with the species name (E. coli) and another with the strain name (K12). Depending on the type of analysis you want to do, you may even separate the genus and species names into distinct columns.

- Export the cleaned data to a text-based format like CSV (comma-separated values). This format ensures that anyone can use the data required by most data repositories.

Discussion 4. Spreadsheet organization.

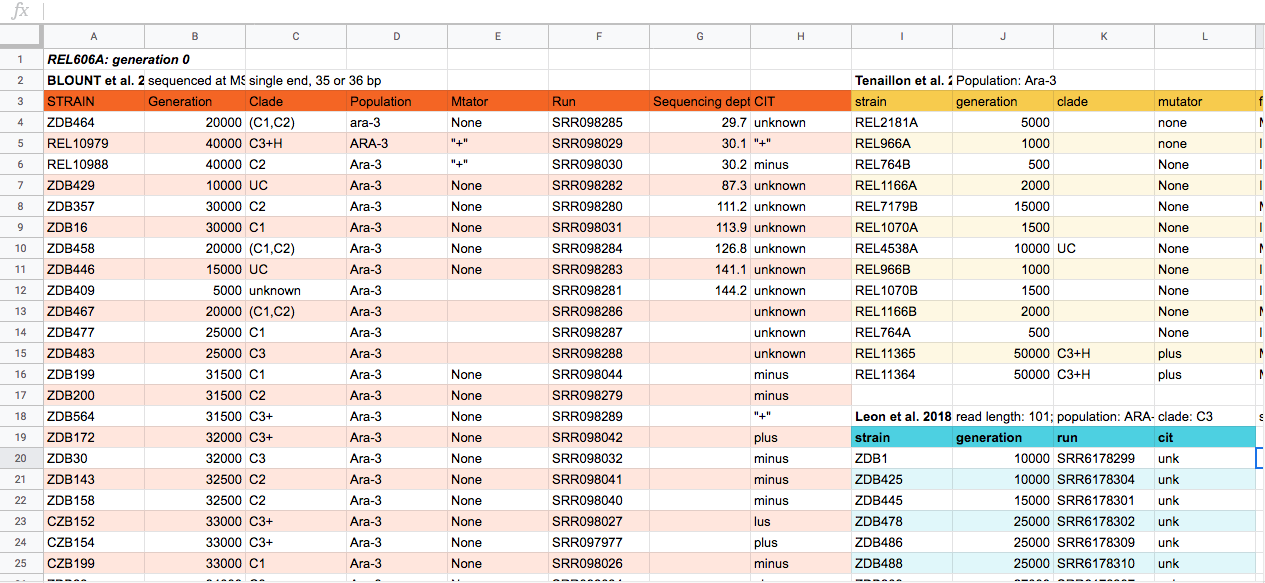

This is a potential spreadsheet data generated about a sequencing experiment. With the person next to you, for about 2 minutes, discuss some problems with the spreadsheet data shown above. You can look at the image or download the file to your computer via this link and open it in a spreadsheet reader like Excel.

Solution

There are a few potential errors to be on the lookout for in your own data and data from collaborators or the Internet. Suppose you are aware of the errors and the possible negative effect on downstream data analysis and result interpretation. In that case, it might motivate you and your project members to try and avoid them. Making small changes to how you format your data in spreadsheets can greatly impact efficiency and reliability when it comes to data cleaning and analysis.

- Using multiple tables

- Using multiple tabs

- Not filling in zeros

- Using problematic null values

- Using formatting to convey information

- Using formatting to make the datasheet look pretty

- Placing comments or units in cells

- Entering more than one piece of information in a cell

- Using problematic field names

- Using special characters in data

- Inclusion of metadata in the data table

- Date formatting

You can keep exploring issues on the metadata file in the Data Carpentry Ecology spreadsheet lesson. Not all are present in this example. Discuss with the group what they found. Some problems include not all data sets having the same columns, datasets split into their own tables, color to encode information, different column names, and spaces in some columns names. Here is a “clean” version of the same spreadsheet:

Cleaned spreadsheet Download the file using right-click (PC)/command-click (Mac).

Further notes on data tidiness

Data organization at this point of your experiment will help facilitate your analysis later, as well as prepare your data and notes for data deposition now often required by journals and funding agencies. If this is a collaborative the project, as most projects are now, it is also information that collaborators will need to interpret your data and results and is very useful for communication and efficiency.

Fear not! If you have already started your project and it is not set up this way, there are still opportunities to make updates. One of the biggest challenges is tabular data that is not formatted so computers can use it or has inconsistencies that make it hard to analyze.

When working in the command line, it is problematic to put spaces in the names of directories and files.

More practice on how to structure data is outlined in our Data Carpentry Ecology spreadsheet lesson

Tools like OpenRefine can help you clean your data.

Key Points

Assigning and keeping track of appropriate unique ID identifiers must be a well-thought process.

Metadata is key for you and others to work with your data.

Tabular data needs to be structured to work with it effectively.

Human microbiome data requires informed consent and confidentiality.